This is the first article in a series of three articles dealing with safety barriers. The first part of this ‘trilogy’ will deal with some general reflections on safety barriers and barrier assessment. The second part will discuss a practical method and example of how this can be done. Thirdly we will discuss some possibilities on how to strengthen the barrier management of an organization.

None of the items discussed pretends to be the ultimate or perfect solution, rather is this meant as an attempt to give an impulse to continuous improvement through reflection, sharing experience and (hopefully) generating some discussion.

None of the items discussed pretends to be the ultimate or perfect solution, rather is this meant as an attempt to give an impulse to continuous improvement through reflection, sharing experience and (hopefully) generating some discussion.

General reflections on safety barriers

One traditional way of dealing with safety in a proactive way is through risk assessments. While risk assessment and its many methods (e.g. TRA, SJA, HAZOP, HAZID) are powerful and important tools in managing challenges, there is a growing realization that the application of the well-known approach of risk as a product of consequence and probability may have some serious drawbacks. This applies especially to the more calculative and quantitative varieties and the decision making that often is related to those. We won’t go into detail of this here and now and rather suggest reading some good literature in this area[1].

One problem with assessments that focus too much on the function of consequence and probability is that they may neglect the influence of uncertainties and assumptions on risk. These, however, may be of greater influence than any of the other factors of your assessment. To illustrate this point, Aven uses the simple example of a throw-of-the dice gamble. Here a calculation of expected risk/value will become totally invalid if one abandons the common assumption that it’s a fair throw, that the die aren’t loaded and the game isn’t rigged.

One way to tackle these uncertainties in a better way is focusing on barriers that are (or are not) in place and discussing the strength of these barriers.

What are safety barriers?

The first thing when discussing and assessing barriers is, of course, an understanding and operational definition. In Norwegian railway safety legislation, a barrier is defined as: “technical, operational, organizational or other planned and implemented measures that are intended to break an identified unwanted chain of events” (Sikkerhetsstyringsforskriften, 1-3). Other standards and legislation contain similar wording; e.g. ISO 17776:2000 (“Guidelines on tools and techniques for hazard identification and risk assessment”) defines a barrier as a “measure which reduces the probability of realizing a hazard’s potential for harm and which reduces its consequence” and explains that “barriers may be physical (materials, protective devices, shields, segregation, etc.) or non-physical (procedures, inspection, training, drills, etc.)”.

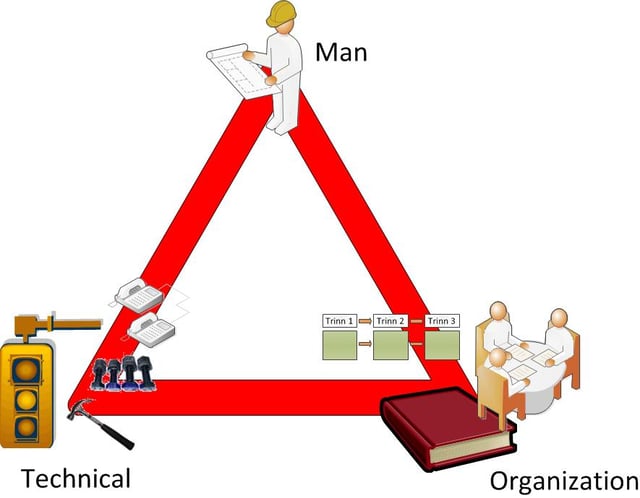

When we speak of barriers in our company we do this from a MTO-perspective: Man, Technical and Organization in relation to each other. This fits very well with the definitions quoted above and within this series of articles we will advocate a wide, call it holistic if you will, approach to barriers. Barriers in our operational definition are the things we put or have in place to prevent unwanted events from happening (i.e. control the hazards) and/or reduce negative consequences of these unwanted events to a minimum.

Misunderstanding about safety barriers

While we don’t claim to ‘own the truth’, we have in our daily practice come across some discussions and misunderstandings about barriers that are wrong, or at least unfortunate.

One of the most important misconceptions is the widespread (especially among regulators) thought “the more the better”. Just not true because of the law of unintended side-effects. More barriers may often mean greater complexity, more possibility for (unexpected) interactions and in effect the creation of new failure modes. This does not mean that one shouldn’t strive for defenses in depth[2], but be aware of the fact that by solving one problem you may very well create new ones.

When talking about barriers it’s important to realize that some barriers are very explicit, like the railing on a bridge. Other barriers, however, are much more implicit like the robust design of your car or your skill in handling the car, forged by formal training and years of experience. This is one reason why some barriers are rather invisible or may not at once strike the beholder’s eye/mind as being a barrier.

There is a misunderstanding (at least among some people we work with on a regular basis) that organizational safety measures aren’t barriers at all. Planning, in fact, is one of the strongest barriers there is. The train timetable makes sure that there are no two trains at the same place at the same moment. Separation in space and time is a very solid safety measure and it’s rather odd not perceiving this as a barrier. Maybe this is because people don’t generally relate the timetable to safety, but rather to punctuality.

Many of the ‘implicit’ barriers aren’t identified in traditional risk assessments because they are ‘hidden’ in the form of assumptions (e.g. competent personnel performing the job) or system design (e.g. most of us take it for granted that they won’t fall through the floor of our offices). You could also consider the competency of the observer. We see many observations for PPE but MUCH fewer in more complicated observations. There is an inverse relation to complexity (i.e.more observations the easier it is to determine).

Another misunderstanding is rooted in the fact that human barriers are seen as weak barriers and therefore cannot be considered as barriers. Humans are often perceived as the weakest link in a system. While humans may have a greater variability than many machines, and are prone to fatigue, distractions and errors of various kinds, it’s also true that humans are flexible, can easily adapt to situations and quite often are a strong factor in ‘saving the day’. Reason and Hollnagel are but two known names in safety who have recently argued that one shouldn’t regard humans only as the source for failure because humans and their variability are just as much the source of success[3].

How good are our safety barrers?

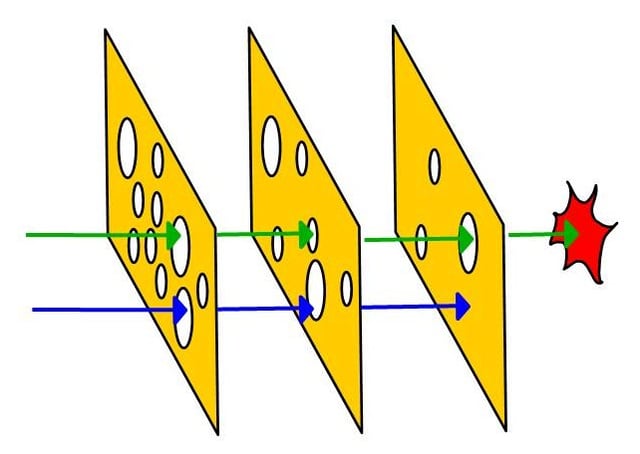

This brings us to the next issue: how good are our safety barriers anyway? Or to put it otherwise, how big are the holes in our Swiss cheese? And where approximately are these holes located? Knowledge about this is an important factor in dealing with assumptions, uncertainties and unknowns.

The thing with barriers is that at they are hardly ever perfect. Barriers such as the ones listed as examples in ISO 17776 can actually fail from one moment to the next. One can choose to follow a procedure or one can decide to take the shortcut, making the rule-barrier useless.

We talked above about the law of unintended side-effects. Barriers may not only be a barrier against hazards, but also a barrier/hinder for the job one is trying to do. It’s tempting then to take shortcuts or find ways to bypass or avoid the barrier, rendering them useless while we may be depending on them.

This mechanism doesn’t only apply to the ‘softer’ barriers, it also extends to technical/physical barriers that can be effective one moment and then ineffective the next. These barriers can be rendered useless in a whim, for example, when we don’t wear seatbelts or safety goggles or when a safety barrier is bridged.

It’s important to see barriers within the context of the system they are placed in. When observing a system, we have to study it as being the combination of man, machines, procedures and other elements. While it’s possible to see each as a separate item with man as one system and the machine as another, and man not being a part of the machine-system, this view of separate systems is not very useful. A man working with a machine creates a new system that is created from several sub-systems. This gives a much clearer view of systems, and also of barriers.

This then also includes the interactions between the various items. The best of machinery (Technical) is useless without an operator (Man), but if he/she isn’t trained properly (Organizational) the output of this system may not be as desired, except by luck.

Assessing the strength of barriers is something a lot can be said about. To just scratch the surface here, one should consider what kind of barrier we are dealing with: M, T or O. Much depends what the barrier shall guard against and how it works. From there, one can distinguish between static and dynamic or active and passive barriers. There is no general rule which is better. This entirely depends on the barrier’s intended function and should be judged accordingly, but one should be alert about dependencies in barriers - e.g. a warning system by itself may not be enough.

Also one should keep in mind that some barriers are pretty situational. When working with one co-worker we may have an understanding that goes way beyond that what is said and our mutual thought pattern may help us to get a job done in no time, even though our communication is sub-optimal. When working with another “less aligned” colleague, the result may be less satisfying.

Another aspect is the consideration of whose responsibility a certain barrier is. This doesn’t necessarily say something about the ‘goodness’ of a barrier, but it does give an indication of the degree of control that you have over the barrier and this should affect the way you value (and depend on) it.

In some cases you may even be in doubt whether you should regard something as a hazard rather than as a barrier. Say you want to work on road safety of your personnel; you can provide them with the best of training and safe cars which you keep in the best of shape through a good maintenance system. Alas you have little control over potential barriers such as the state of the roads and the competence of other road users. Regarding these as hazards is a choice that depends upon your assessment, and maybe you want to consider additional barriers.

Decision making - what barriers to choose?

Resources tend to be limited, so one really important question that almost always pops up: what shall we spend our money on?

The first requirement in decision making, of course, is recognition of the hazard, the realization that something has to be done and the will to actually set things in motion to create barriers. Intellectually understanding the risk but doing nothing just isn’t enough.

Having come so far, everything of course depends on the specific case; what shall we guard ourselves against. But there are some general rules of thumb in safety that are usually wise to follow:

- Reducing probability tends to be more effective than reducing impact, but one cannot entirely discard the latter, of course. Air bags are smart having, even if we never hope to use them.

- Follow the typical hierarchy in safety measures: removing hazard sources trumps collective measures trumps individual measures trumps personal safety gear. If only because working in a quiet environment is so much comfortable than walking around with ear plugs all day long.

- Building in safety and barriers from the start (design or planning) is cheaper and more effective than adding these afterwards.

- See things in perspective with other objectives in order to avoid conflicts as much as possible. Remember the law of unintended side effects?

Cost/benefit, of course, is an important factor to consider and sometimes one may consider accepting a risk. While this may sometimes be acceptable, may often meet political or moral objections. Also, it’s sometimes the question how well-considered some cost/benefit assessments actually are. Often one sees a penny wise/pound foolish approach where the immediate out-of-pocket costs appear to dominate the decision. After all, it’s very easy to decide implementing the more individually oriented and quick to implement ‘barriers’ (prescribing personal safety gear, making a new rule, enforcing existing rules) instead of preferring the slower, but often more robust technical or organizational barriers that go deeper than the surface, but require more effort, time and follow-up.

Common sense is a rather touchy and messy concept which we want to avoid, yet it has to be said that gut feeling can be a good indicator for a decision that has to be taken. But make sure to critically assess these primary or instinctive reactions towards a decision in a systematic way: what reasons are there for or against. And don’t forget: whatever you will decide upon, it will have effect on other things. Silver bullets in safety are rare, or probably non-existing.

---+---

Much more could and should be said about this theme, but let’s wrap it up for now. Next time we’ll take a look at one way this can be done.

Biography

Carsten Busch has studied Mechanical Engineering and after that Safety. He also spent some time at Law School. He has over 20 years of HSEQ experience from various railway and oil & gas related companies in The Netherlands, United Kingdom and Norway. These days he works as Section Head Safety and Quality for Jernbaneverket’s infrastructure division.

Beate Karlsen has studied Occupational Health and Safety at Haugesund and at the Stavanger University. She has been in various OHS functions in Jernbaneverket and works currently as Senior Advisor Safety in Jernbaneverket’s infrastructure division.

[1] Terje Aven from Stavanger University, among others, has done some great work in this area recently.

[2] A good deal of regulations (e.g. the Norwegian railway legislation) even prescribes the presence of several independent barriers in order to prevent single failure accidents.

[3] See for example Reason’s “The Human Contribution” or Hollnagel’s ETTO book