The measurement revolution began in my prime. I was working with Industrial Engineers, a nice bunch, with the world-view that everything can be designed to run smoothly. We were a part of the Quality Revolution. I had just gone to see W. Edwards Deming for the third time, eager to hear his thoughts on measurement.

Deming was a statistician who, like me, saw the world in terms of variance. We don’t look at absolutes, we look at differences. Therefore, when viewing injury data I look for change over time, variation across work units, comparisons to industry top quartile, and the like. Within the groups of numbers, quite interesting and actionable sources of variation lie.

When someone gets injured, many look at the investigation for answers as to what to change. All well & good. But what about the dozens of stories, the dozens of variations in human and machine behavior that, if measured, would have revealed a basis for action before the injury? A good measurement system can save a world of hurt…literally.

But if you don’t understand variance, your view of the world blinds you to risk. Deming said that one of the greatest threats to organizational quality (and safety, from my perspective) is “single data-point management” too often practiced by managers who don’t understand the concept of variability. Unfortunately, in the safety world I see too many single data-point managers.

I recall a story of a man in South Africa who was caught without his safety gloves by his supervisor who immediately fired him based on this single data point. The safety manager refused to accept the firing because the man had 3 young children. Upon interviewing the man he found out that he had removed his gloves temporarily to clean his safety glasses for better visibility.

FISHING BADLY

I feel bad for my son because he likes fishing and I’m not very competent in the sport. We go to the lake, he throws out his line and waits to hook that one fish of the unseen thousands.

Single data-point management resembles that type of fishing. The manager or supervisor, or you, yourself, have a list of measures consisting of outcome data (such as injuries), or instrumentation data (from machines or via other forms of technology) resembling the kinds collected on fishing trips. Also, walk-arounds are like fishing trips where you’re fishing for violations of rules. You’ve got your line out and are trolling for rule-breaking behavior.

Measurement is often used that way much too often. You don’t pay attention to thousands of safe behaviors, but just hunt for violations. As long as the measures come back clean, you credit an absence of bites. So you continue looking for that instance in which the data gives you what you think is a clear danger signal and you yank on the line to attempt to hook the violation.

Once, my sons and I went fishing with a guide on a chilly day in Florida. The fish were not biting because it was so cold, so the guide threw some “chum” into the water (something like candy for fish), to draw them in, so my young sons could score some catches. And, fortunately for our vacation, we did catch a couple of small hungry fish.

Once, my sons and I went fishing with a guide on a chilly day in Florida. The fish were not biting because it was so cold, so the guide threw some “chum” into the water (something like candy for fish), to draw them in, so my young sons could score some catches. And, fortunately for our vacation, we did catch a couple of small hungry fish.

Sometimes when managers see injuries occurring, but lack valid or accurate measurement systems capable of revealing root causes, they may begin throwing safety’s version of “chum.” They walk around trolling frequently observing the smallest fish; that is, catching the smallest violations.

BUT… these apparent safety successes actually are an ILLUSION.

You are made to think you are doing something productive, when in fact you’re actually unintentionally promoting injuries; and diminishing your managerial skills in the process.

THE ILLUSION

Think about it. Early in your career as a lead, supervisor, and/or manager you probably didn’t start your new job thinking: “I’m going to be pissed off all the time and scold employees.” Rather probably you approached your assignment thinking: “I’m going to be the calm, understanding boss.” The measurement illusion you picked up by chumming the waters during your fishing trips turned you into a scolding and ranting supervisor.

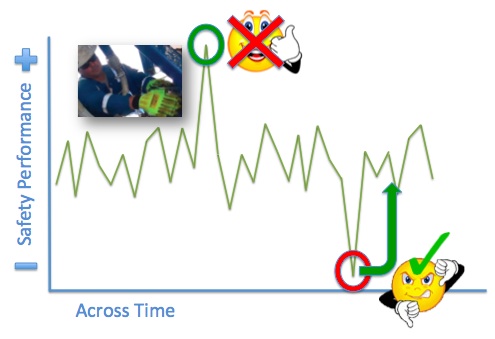

The reality is that each of your employees has good moments and bad moments. All have moments of good safety performance, making an effort to keep themselves and others safe. At other times they may have moments when they take risks, intentionally or not. Most of the time employees vary around an average set of behaviors that, for the most part, keep them safe and productive.

Now, as a manager who fails to pay attention to variance, you tend to overlook this average set of behaviors generally responsible for keeping employees safe. What you noticed early in your leadership career on your “fishing expeditions” were the outliers in performance.

You noticed when a particular employee promoted safety in some exceptional way. Perhaps, tired of waiting for an engineered fix, the employee built a guard on a piece of machinery that had worn down and presented a hazard. You noted that behavior and made a clear effort to praise the employee, perhaps even recognizing that effort in front of the work team.

But you didn’t understand variation; you praised a single data point. This exceptional performance was an outlier; not what that employee always did. So the employee’s safety performance regressed back to the employee’s average set of behaviors. You saw the employee’s safety performance drop and didn’t recognize this as a natural occurrence. Perhaps the next day you see the employee take a shortcut by walking over some pipes. You think to yourself “I just praised him and now he’s doing something risky.” You become less likely to use praise in the future because you’ve just been punished for being positive. But your interpretation is an illusion, because it was not your praise that caused the drop. It happened naturally.

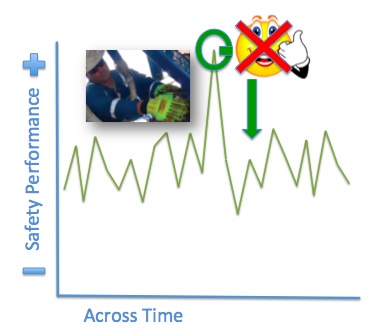

Now consider what happens when you go trolling for violations. You search far and wide for risk, ignoring the average safe practices going on all around; or worse, think that if you praise safety, you’ll promote injuries. Then you catch an employee who does something obviously risky. Perhaps, he had his safety glasses around his neck while engaging a machine. He had taken them off to clean them and check some paperwork and forgot to put them back on. So you yanked the line and caught him. You were upset and disappointed in him and let him know it by reprimanding him.

Well, in the past, this employee probably had always worn his Personal Protective Equipment (PPE). This lapse was a rarity. In fact, after this incident, this employee wore his PPE consistently like he always had. You may have perceived “I just scolded him and his safety performance increased”. You become more likely to scold in the future because your use of scolding and/or discipline has just been reinforced. But that is an illusion because your scolding did not produce the improvement; it happened naturally.

Your punitive management style is an insidious superstition because slowly, at first, it shaped your increasing use of negative consequences like scolding and discipline. Eventually your management behavior has become like a fishing expedition-- looking for opportunities to use unpleasant consequences -- under the illusion that they work. Sometimes that can shape you into quite the grumpy dude. Even worse, you’re not stopping injuries.

THE DAMAGE

Fishing expeditions frighten employees along with the measurement system you use. This damages a safety culture. Think about it from the employees’ perspective. When they see you coming, they anticipate punishment. When they see a measurement taken, they worry it will be used against them. Nothing positive there!

Folks get nervous and distracted. They hide their behaviors. Peers teach one another how to avoid getting caught. (I’d do that if I were a fish who could talk.) The culture deteriorates. Injuries increase.

Don’t be fooled by this illusion. Instead, look for variation, discover its source, and manage it. Better fisher folk than I use sonar in their boats. Sonars bounce sound waves down toward the lake bottom. Schools of fish reflect this wave back to the sensors and show up on the sonar screen, giving you a good idea of where fishing may be productive.

A good measurement system scans your operations objectively, looking for pockets of variation that may reflect hazards and risks. When you find this variance, use your problem solving tools to cast your net over the potential problem and solve it… before harm results.

But you can only look at variation and its sources if employees are participating in safety measurements. Outcome data such as injury rates are not sufficiently sensitive. Additionally, your own walk-arounds probably reflect your personal biases and are confounded, thereby, by your presence. Instead, turn to your employees who should be able to provide the insights into the risky behaviors and conditions that set the stage for them. They know the sources of variance; they can collect those data in a no-name/no-blame system of the type found to be successful in Behavioral Safety systems and they can play a part in reducing that variance.

After all, isn’t having the fish just jump in the boat a fisherman’s dream?