It is time to point to the elephant in the room and acknowledge 'Pencil Whipping' during data collection such as with Behavior Based Safety observations. Pencil Whipping is a euphemism used to describe when workers, supervisors, and, yes, safety managers, fill out observation cards, sometimes in great numbers, without actually conducting the observation (much less providing the critical feedback). This article will seek to understand and provide solutions for the environment that causes pencil whipping by reviewing research data and case studies for clues into this potentially deadly practice.

Forms, forms, forms

I looked at a supervisor’s office at a major construction site. It was more overloaded than mine (yet much neater). The desk was full of paper; forms upon forms to fill out. These included operational forms, HR forms, quality checks, surveys from upper management, and, of course, a plethora of safety forms.

Job Safety Analysis (JSA) forms to be done every shift, first aid forms, safety audits, injury investigation reports, and safety observations like STOP or BBS, safety work orders, safety suggestion forms, process safety checks… I asked the supervisor when he had time to go out into the site. “And give up my desk job?” he replied jokingly.

Employees are increasingly asked to complete forms. Permits, equipment inspections, work orders, and behavioral observations are just a few that focus on safety.

Now all these forms are designed to reduce injuries. A well designed behavioral observation card not only provides the “script” for reinforcing feedback, it also can identify risk and give the observer an opportunity to write a comment that identifies the cause of the actions and suggest fixes that the whole work team can learn from.

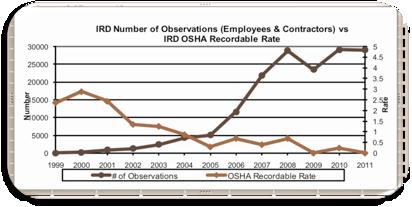

These forms serve an important purpose, and the more of them that are completed, research and real-world applications show, the more injuries are reduced.

This is because more observations result in more one-on-one feedback, which is the most powerful motivator of safe behavior out there (and the cheapest too). As an added benefit, when the observations cards come in, they can be analyzed and trended to find the areas of risk that are most prominent on the job. When these areas are targeted for improvement, equipment is updated, protection is worn, and short cuts are no longer needed. This reduces the threat of injury as well.

That is, if the forms are actually used for this purpose. Enter the Pencil Whip.

“Pencil Whip” is a verb, which means it’s an action, something someone does, and something someone does intentionally. Yes, the term is so prolific that it made the Wikipedia dictionary: “To complete a form, record, or document without having performed the implied work or without supporting data or evidence.” In Australia’s vast mining industry they call it “Tic and Flick”. The idea is that you are filling out forms and making up the data so fast that the end of your pencil is whipping in the air.

How do you know data is getting Pencil Whipped?

Look at your behavioral observation data for big jumps in cards in just a couple of days. Look at those cards and you’ll see multiple cards turned in at the time. The same person would do these cards in just a couple days (if they are good they will use different pens and different inflections in the handwriting, but not usually). They certainly do not take the time to write in comments or suggestions.

You’ll also notice that at-risk behavior is rarely reported on the pencil whipped cards. Indeed, if your at-risk behavior percentage is below 2% on nearly all your behaviors, you’ve got a pencil whip problem.

Perhaps the easiest way to find out about pencil whipping is just to ask. Most will admit to some pencil whipping but typically you’ll hear “supervisors tell us to do observations because we need to make our numbers,” or “I do the card afterward from memory,” or “I do the cards to get in the drawing for the gift cards, I nearly forgot before the deadline.”

Or, simply ask yourself. Admit it, you already know. In fact, you may be enabling pencil whipping. Yup, you. Because having a lot of observations makes you look good!

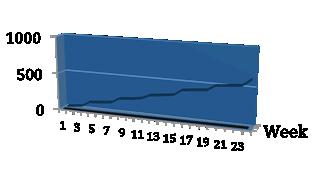

The case of the 1000 observations a month

A mining construction general contractor had the best intentions when the experts told him to monitor his company’s behavioral observation process measures. He was coached to ask about the number of observations his contracted workforce was engaging in. When I went to meet with him after the process was in place for over a year he was sure that behavioral observations did not work. I would have drawn the same conclusions.

“We are getting over 1000 observation cards turned in a month, yet we keep getting around two incidents each month.” He concluded, “It doesn’t work in construction.” He went on to describe a number of times when his safety people reviewed cards from the previous day and saw that an action was done safe 100% of the time.

“Walking under loads was a big one, it’s a real risk being taken on a construction site with cranes everywhere. Well dozens of cards were turned in indicating that no one was walking under these cranes, 100% safe.” His teeth clinched a bit, “The day these cards were turned in my safety guy went out to that work site and saw nearly all the workers walking under a crane. There were no barricades or markings. In fact that pathway was the only route between two work areas. There is no way these cards are accurate. The employees only want to make each other look good.”

It was time to ask questions. “Confidentially, tell me what’s going on.”

Employees: “I never heard of the program.” “I’ve not been observed.”

Then I started asking questions up the line.

General Contractor: “I did what I was coached. I asked to see the contractor participation numbers.”

Construction Manager (reporting to the General Contractor): “I told the contractors to get me their behavioral observation numbers.”

Contractor Manager: “The General Contractor wants the numbers, I pressed my supervisors to get those observations done so we looked good. I don’t want to be the one that loses this contract over a safety program.”

Supervisors (when presented with the dozens of cards in their handwriting): “I filled out the cards for the employees…at the end of shift.”

Translation: Pencil Whip.

Production is a numbers game, and it should be, but when ‘Getting the numbers’ gets applied to safety, well, you get the numbers.

Going “all-in” with Incentives

Another well-intentioned tactic to encourage observations is to offer incentives. In my travels I’ve seen a number of increasingly innovative incentives. Raffles seem to be the most popular because they seem to not really be an incentive; instead it’s a game.

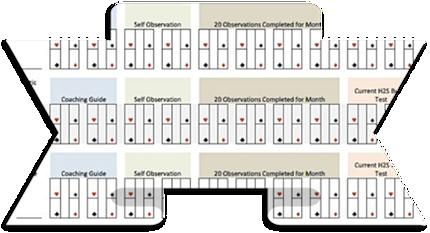

A contractor organization at a refinery had developed a very popular game similar to Texas Hold ‘Em to promote observations. It was pretty cool. At the end of the month you received a playing card for every 5 observations you turned in (up to 4 cards). You could get 2 additional cards for self-observations, 2 cards for doing observation training modules, and 2 additional for special safety programming like participating in inspections. The employee who had the best poker hand won a $50 gift card.

This game generated a lot of observations, but they came in waves, right before the end of the month. Now this company has a great behavioral safety program and their injury rate is near zero – amazing for a construction company. But if you look at cards done in the 4 days leading up to the end of the month you get the tell-tale signs of pencil whipping (one person turning in multiple cards a day, all 100% safe, no comments).

You get what you pay for.

How Pencil Whipping Evolves

An excellent behavioral safety program had been developed in a company operating a fleet of ocean research vessels. It was replete with common observation cards, online observation card recording software, electronic training, local steering teams, and a second-to-none data analysis program. Mariners would retrieve a card, do their observations, give feedback, and then enter their observation data themselves on an on-board computer connected to the company intranet.

Some vessels had better safety records than others and some were getting more observations recorded than others. In an effort to increase observations on some vessels one of my students helped this company devise a shorter observation form. Their original form had 18 items to observe and score safe or at-risk. He went through their incident and first aid files to find the 8 behaviors most likely to end up in an injury. They then adapted the cards to include only those 8 behaviors and put these cards on the decks of three vessels with the word that these cards are easier and quicker to complete.

Well, it didn’t work. The observation counts did not go up. However, an interesting thing did happen: they kept reporting on the old behaviors. That’s right even though the new cards dropped 10 of the behaviors, only listing the 8. When the employees went to the computer software, which had not been changed so it still listed the 18 items, they reported on all 18 items, not just the 8.

In our interviews afterward we were told, “Well, the guys have used the cards for so long they just rely on their memory to enter the observations.” They were no longer using cards at all.

It occurred to me that this is how pencil whipping may evolve. At first, employees use the card and do a real observation of a peer. They then most likely provide that person feedback and the data they turn in is accurate.

When the cards get memorized I would imagine that the observations still take place but probably rather quickly. Feedback is less likely to happen over time. When the data is finally recorded on a card or, in this case, in the computer, accuracy goes down. With memory comes forgetting. We know that only 7 +/- 2 pieces of information can stay in short term memory at any one time and those memories only last a couple minutes, and that’s when they don’t get interfered with by other things demanding attention.

Because we are likely to forget we tend to rely on our overall impression of the person, the type of work being done, or how safe things tend to be out there. This is called the “Halo Effect,” not because we see the person as “angelic” but because we let our overall impression of the person or situation help us guess. Indeed, we end up guessing and accuracy goes away further and we miss the opportunity to identify risks.

Then, follow the trend here. The employee or supervisor now has experience not using the card yet still getting credit for turning in an observation. They figure out quickly that the only thing they really get credit for is turning in a completed card or, in this case, entering data. This can be done, they find out, without even doing an observation, much less by giving feedback.

So the pencil whip is shaped up nicely and the safety observation program is in jeopardy and worse, people’s lives are more in danger.

Pencil whipping occurs because it is the path of least resistance. Don’t blame the ‘whipper’. In fact, your observation form process is perfectly designed to produce pencil whipping. Redesign it to reinforce the conversations it is designed to facilitate.

How to stop pencil whipping

a) Name the Demon.

In the bible, Jesus gets rid of demons by calling out their name. There are parallels in every religion and tribal custom. The wisdom rings true here. Bring pencil whipping out of the closed offices or workstations and into the light. Admit it is a problem by name. Don’t accuse, instead inquire – “How can we change this?”

b) Drop Incentives and Quotas – Go to rewards.

Incentives are planned and advertised as a positive consequence of action. Rewards, on the other hand, are seemingly spontaneous acts of gratitude. They don’t have to be big, they have to be fair, and they have to be based on the outcomes of the behaviors the employees can control. They should specify the behaviors that happened and offer a genuine “thank you” or recognition.

In the case of behavioral observations, rewards should be given for the identification of at-risk behaviors and comments, especially those that lead to fixes.

c) Provide group feedback abundantly. Make visible changes.

Reinforce the notion that doing an accurate observation, giving feedback, and reporting all make a difference. You show that life is better because of their actions…the workplace is safer and things are changing. Provide the group feedback of their success: rising observation counts, higher participation, injury reduction, and most of all, at-risk behaviors identified.

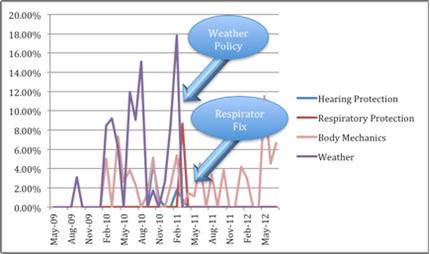

A contractor fitting insulation at a refinery has an excellent behavioral observation program effective at identifying risk. One of the risk behaviors that kept showing up was working outside in hazardous weather (see the graph). The work team was thanked for providing the data to show that this was an unnecessary risk that workers felt they had to take. Management then instituted a clear policy statement on work procedures in inclement weather, including stopping work.

After employees experienced this victory they then began reporting at-risk behaviors around the (non)use of respirators. This got fixed quickly by changing a chinstrap that was uncomfortable. In both cases, these behaviors were now done safely in 100% of reported cases. As a result, the employees were more likely to identify other, more personal areas of risk like body mechanics. This reporting behavior, in my opinion, is the opposite of pencil whipping.

d) Change your Behavioral Observation Card Frequently.

Sometimes it’s as simple as the old card had just gotten stale. You’ll have to fight the impulse to use the same card across all work units forever. The impulse comes from the great data analysis you can get from long-term common observations (I fall prey to it myself as a researcher).

Instead, you may want to follow the example of a national grocery distribution company who designs changes into their behavioral observation process. In their process the employee team chooses only 3-4 items to appear on a card. Observations and resulting feedback is easy. The data are trustworthy. The % safe for each behavior is posted prominently in the employee lunch area and is mentioned daily at the beginning of shift. Once one of the behaviors reaches 98% safe for three consecutive months a celebration ensues and the behavior is “retired”. The team then picks a new behavior to take its place, the card changes, and the system begins anew. Pencil whipping does not ever factor into the equation.